-

今日人氣

-

累積人氣

-

粉絲數

-

回答數

-

文章數

病毒也會「生病」

病毒也會「生病」 證明是生物

病毒到底算不算是「生物」?這個問題生物學界爭議數十年尚無定論,關鍵在於病毒不像一般生物,無法「獨立」進行新陳代謝與繁殖後代。然而病毒也有基因,也會演化,似乎又具備生物的基本條件。

主張病毒屬於生物的學者近來軍心大振,因為有一個「大塊頭」出面力挺:法國學者發現一種「大型擬菌病毒」(mamavirus),體型遠大於一般病毒,且居然會「生病」,被一種「噬病毒病毒」(virophage)感染。

研究論文刊於最新一期的英國《自然》周刊,作者之一法國國家科學研究中心(CNRS)學者克拉維希說:「病毒當然是生物,它會生病的事實更強化了這個信念。」

克拉維希的同事哈烏在二○○三年研究一種先前被歸類為細菌的生物「Acanthamoeba polyphaga」,發現它屬於病毒,只是體型遠大於同儕,擁有九百多個會調控蛋白質的基因,是先前已知最大病毒的三倍,甚至傲視許多細菌,因此被歸類為「擬菌病毒」(mimivirus)。

後來哈烏又發現體型更勝一籌的大型擬菌病毒,並連帶找到一種只有廿一個基因的新病毒,兩者關係有如地球與繞地人造衛星,因此後者被暱稱為「史潑尼克」(Sputnik,史上第一顆人造衛星)。當大型擬菌病毒侵入阿米巴原蟲建立「病毒工廠」,史潑尼克會伺機而動接管工廠,生產自家的基因物質,讓大型擬菌病毒欲振乏力,可視為一種「噬病毒病毒」。

史潑尼克像寄生蟲一樣,以大型擬菌病毒為宿主,而且有三個基因很可能是攫取自宿主,顯示它能夠在病毒之間橫向傳遞基因,一如「噬菌病毒」傳遞細菌的基因。哈烏相信巨型病毒與噬病毒病毒普遍存在海洋浮游生物體內,對海洋營養循環相當重要。更新日期:2008/08/08 09:20

【中國時報 閻紀宇�綜合報導】

原文

'Virophage' suggests viruses are alive

Evidence of illness enhances case for life.

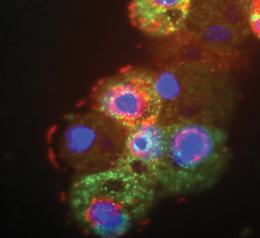

Giant mamavirus particles (red) and satellite viruses of mamavirus called Sputnik (green).REF. 1

Giant mamavirus particles (red) and satellite viruses of mamavirus called Sputnik (green).REF. 1The discovery of a giant virus that falls ill through infection by another virus1 is fuelling the debate about whether viruses are alive.

“There’s no doubt this is a living organism,” says Jean-Michel Claverie, a virologist at the the CNRS UPR laboratories in Marseilles, part of France’s basic-research agency. “The fact that it can get sick makes it more alive.”

Giant viruses have been captivating virologists since 2003, when a team led by Claverie and Didier Raoult at CNRS UMR, also in Marseilles, reported the discovery of the first monster2. The virus had been isolated more than a decade earlier in amoebae from a cooling tower in Bradford, UK, but was initially mistaken for a bacterium because of its size, and was relegated to the freezer.

Closer inspection showed the microbe to be a huge virus with, as later work revealed, a genome harbouring more than 900 protein-coding genes3 — at least three times more than that of the biggest previously known viruses and bigger than that of some bacteria. It was named Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus (for mimicking microbe), and is thought to be part of a much larger family. “It was the cause of great excitement in virology,” says Eugene Koonin at the National Center for Biotechnology Information in Bethesda, Maryland. “It crossed the imaginary boundary between viruses and cellular organisms.”

“There's no doubt that this is a living organism. The fact that it can get sick makes it more alive.”

Now Raoult, Koonin and their colleagues report the isolation of a new strain of giant virus from a cooling tower in Paris, which they have named mamavirus because it seemed slightly larger than mimivirus. Their electron microscopy studies also revealed a second, small virus closely associated with mamavirus that has earned the name Sputnik, after the first man-made satellite.

With just 21 genes, Sputnik is tiny compared with its mama — but insidious. When the giant mamavirus infects an amoeba, it uses its large array of genes to build a ‘viral factory’, a hub where new viral particles are made. Sputnik infects this viral factory and seems to hijack its machinery in order to replicate. The team found that cells co-infected with Sputnik produce fewer and often deformed mamavirus particles, making the virus less infective. This suggests that Sputnik is effectively a viral parasite that sickens its host — seemingly the first such example.

The team suggests that Sputnik is a ‘virophage’, much like the bacteriophage viruses that infect and sicken bacteria. “It infects this factory like a phage infects a bacterium,” Koonin says. “It’s doing what every parasite can — exploiting its host for its own replication.”

Sputnik’s genome reveals further insight into its biology. Although 13 of its genes show little similarity to any other known genes, three are closely related to mimivirus and mamavirus genes, perhaps cannibalized by the tiny virus as it packaged up particles sometime in its history. This suggests that the satellite virus could perform horizontal gene transfer between viruses — paralleling the way that bacteriophages ferry genes between bacteria.

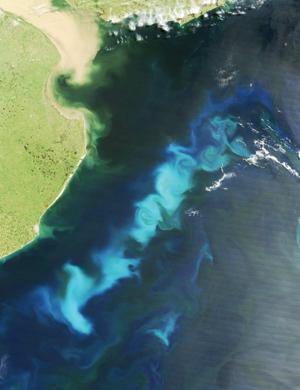

Virophages may be common in plankton blooms.J. SCHMALTZ/NASA

Virophages may be common in plankton blooms.J. SCHMALTZ/NASAThe findings may have global implications, according to some virologists. A metagenomic study of ocean water4 has revealed an abundance of genetic sequences closely related to giant viruses, leading to a suspicion that they are a common parasite of plankton. These viruses had been missed for many years, Claverie says, because the filters used to remove bacteria screened out giant viruses as well. Raoult’s team also found genes related to Sputnik’s in an ocean-sampling data set, so this could be the first of a new, common family of viruses. “It suggests there are other representatives of this viral family out there in the environment,” Koonin says.

By regulating the growth and death of plankton, giant viruses — and satellite viruses such as Sputnik — could be having major effects on ocean nutrient cycles and climate. “These viruses could be major players in global systems,” says Curtis Suttle, an expert in marine viruses at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

“I think ultimately we will find a huge number of novel viruses in the ocean and other places,” Suttle says — 70% of viral genes identified in ocean surveys have never been seen before. “It emphasizes how little is known about these organisms — and I use that term deliberately.”